The best thing to happen at the University of Wollongong for some time has been the establishment of the UOW Feminist Society (FemSoc) and the creation of its ‘Free School’. At the start of 2013 the University axed its Gender Studies Major, declaring it was not “cost effective”, due to a lack of interest. Yet despite the supposed unpopularity of the course, students were upset with the decision, and as soon became obvious, were actually interested, engaged and eager to learn about gender and feminism. In response to the cutting of gender studies, some students undertaking Philosophy of Feminism decided to form a gender inclusive Feminist Society. The group has since been run by students and academics, giving many people a chance to participate in feminist activism, to raise awareness of feminism and to create safer social spaces to talk about feminist issues.

The major initiative of FemSoc has been its Free School lecture/workshop series. As Claire Johnston explains; “The process of establishing the Free School was pretty straight forward: a room on campus was booked for 12.30 each Wednesday, academics doing research on issues related to gender were asked if they would like to give a half-an-hour lecture followed by discussion, posters were designed and Facebook events were created. There were deliberately few guidelines given to academics wishing to present or run a lecture or workshop”. Soon lectures and workshops were also being run by students.

Free School was initially developed as a creative way of protesting against the gender studies cuts. It was hoped that if the university saw students putting aside an hour of their lunch every Wednesday it would clearly demonstrate they had an interest in learning about gender and feminism. However, as the free school took off, it soon established itself as an alternative academic project, replacing and reshaping gender studies. According to Jane Aubourg, the University’s response is no longer the Free School’s highest priority. “Initially, we wanted to show the University’s administration that there definitely is student interest, as well as a societal need for the study of gender. But now we know that even if the major was reinstated students wouldn’t stop coming to our workshops and academics wouldn’t stop giving talks – simply because the Free School covers areas of feminism the University of Wollongong would simply never offer.”

For Claire Johnston; “What was clear to us in FemSoc was that the investigation and study of gender was crucial to abolishing patriarchy on our campus and in the society we lived in. On the one hand, we were genuinely upset that the Faculty of Arts was dissolving the Gender Studies major – after all, women’s studies and gender studies were born out of struggle. Removing these courses would reverse years of campaigning to have the study of gender acknowledged as an important area for both research and teaching. However, after some consideration and discussion with academic staff, we knew that there were significant problems with the way the Gender Studies course had been run, such as the dominance and influence of the Centre for Research on Men and Masculinities. We concluded that fighting for the course to be reintroduced in its previous form wasn’t especially appealing”.

As one observer of the Free School setup explains; “It’s not even a lecture, or a workshop, or seminar, or any other teaching format that universities are promoting to disguise thinning staff numbers, bulging class sizes, and steady disenfranchisement. It’s a protest – all these students are learning from qualified academics and they ain’t paying a buck.” And as Erin Prior describes; “You can sense the passion in the air, you can almost hear peoples’ brains processing the ideas being discussed, and it’s amazingly, ridiculously engaging. It is learning without obligation”.

Claire Johnston also explains how; “FemSoc is a diverse group with diverse politics, and although some of us had experience in campaigns on campus, we decided that running a series of free, weekly public lectures and workshops was a relatively simple and accessible project that would give us a platform to not only publicly condemn the university’s decision to cut Gender Studies but also to open a space for discussion of issues to do with gender. We have been astonished by its consistent popularity with students and staff. More importantly, we have been impressed by the space it has provided for developing and testing our ideas, not just about issues revolving around gender, but on the problems of the university and tactics of resistance”.

UOW FemSoc has now successfully run a year’s worth of diverse lectures and workshops, spanning topics such as the history of feminism, the ‘white wedding’ narrative, ecofeminism, sexual ethics, consent and deceit, trans 101, women in comedy, the representation of Muslim women in the media, men and feminism, sexual violence in Tahrir Square, gender, democracy and ethics in political theory, white women, indigenous women and feminism, anti-rape protests and media activism in India, sex, consent and the media, and much more. As well, collaboration with academic staff has led to the creation of the Feminist Research Network – a network of teaching and research staff, who share and collaborate on research into gender and sexuality in areas as diverse as law, philosophy, literature, creative arts, sociology, cultural studies, and more.

In May, FemSoc also ran Consent Week – a campus-wide week of anti-victim blaming, sex-positive, anti-sexual assault campaigning, with a range of events to raise awareness about the pervasiveness of sexual assault, both on campus and in the community. Law student and one of the Consent Week/FemSoc organisers, Olivia Todhunter, was eager to use the event to develop more widespread understandings of the ways in which consent is defined by the law. “There is something fundamentally wrong with how we are educated to think about consent, healthy sexual relationships and sexual assault…” Olivia said. “I would really like to make sure people know how consent is defined – not only before the law, but in the context of everyday sexual interactions”. Consent Week promoted ‘safe sex’— where ‘safe’ means not just protecting against sexually transmitted infections, but also involves making sure all participants feel safe in sexual encounters. “The issue of consent came up at our first-ever meeting,” explains Jessie Hunt, another Consent Week/FemSoc organiser. “We started talking about the fact that around one in five women will be sexually assaulted in her lifetime, and how alarming that statistic is . . . as we talked, we realised that consent is just left out of so many discussions about sex — consent doesn’t rate a mention in pornography, or in our high school health curriculums”. Consent Week featured free workshops and included a Consent Day Carnival, with show bags containing information about consent, condoms, dams and lubrication, as well as bands and booths with information on global consent campaigns.

FemSoc has also held many planning meetings, informal discussions, skill shares, stalls, and other events. At the end of 2013 FemSoc marked its first year with an end-of-year festival – a night of film, music and discussion.

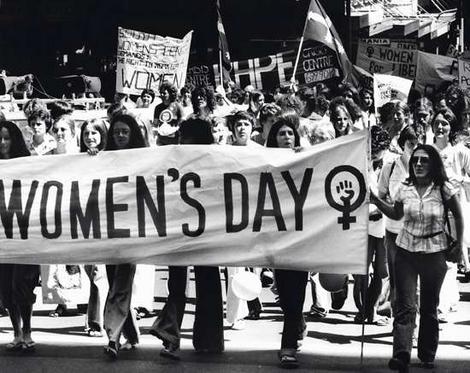

As Claire Johnston details in an article she wrote about FemSoc; “The level of popularity and engagement we have experienced with free school says several interesting things about feminism, students, the university and education more broadly. Firstly, the re-emergence of a feminist movement in recent years in both Australia, mostly in the form of the Slut Walks and Reclaim the Night demonstrations, but also across the world, particularly in India, has had a local impact on campus. FemSoc is certainly a product of such a renewed focus on feminist activism and themes from this movement such as rape culture, victim blaming and consent have been consistently brought up in Free School lectures or workshops. The enthusiasm and numbers of students participating perhaps suggests a change in how young people (although it should be noted that it is not just young people attending) are viewing feminism in the face of years of anti-feminist backlash.”

“Secondly, the popularity of Free School says something about ‘the student’. Constantly I am being told that most students are uninterested in politics, activism and education outside the realm of learning their degrees.” Yet, the “level of support and engagement we have received from students and staff within the university has suggested that people are engaged, willing to learn and to participate. Even more exciting is that they are willing to dissent.” And; “The most exciting potential Free School has is to transform a small part of the deeply alienating and stressful institution that is the university, into a fun, engaging and caring space. Although we began this project to discuss and take action on gender, it has become a project where we can challenge the dominant forms of pedagogy and spread dissent to how our education is structured.”

Congratulations to all of the wonderful women and men who have created and sustained UOW FemSoc, you are an inspiration.

You can find out more about UOW FemSoc and its activities via Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/UOWFemSoc